Digital pathology is a key enabler of transformation and consolidation in pathology. But how far should we take the laboratory out of the hospital? Jane Rendall, UK managing director at Sectra, reflects on a conversation with a cellular pathologist that might make healthcare leaders pause and think about consolidation strategies.

Digital pathology is like any tool – including dynamite. In the right hands it can be really good and useful. In the wrong hands it can be quite destructive. Some managers think that installing digital pathology will solve all their problems without even modifying or adapting patients’ pathway. That’s not going to work.

With digital transformation at the top of the healthcare agenda, it can be easy to think that technology can solve the problems faced in disciplines like pathology. Digitise and then everything becomes easier, faster and better connected – right?

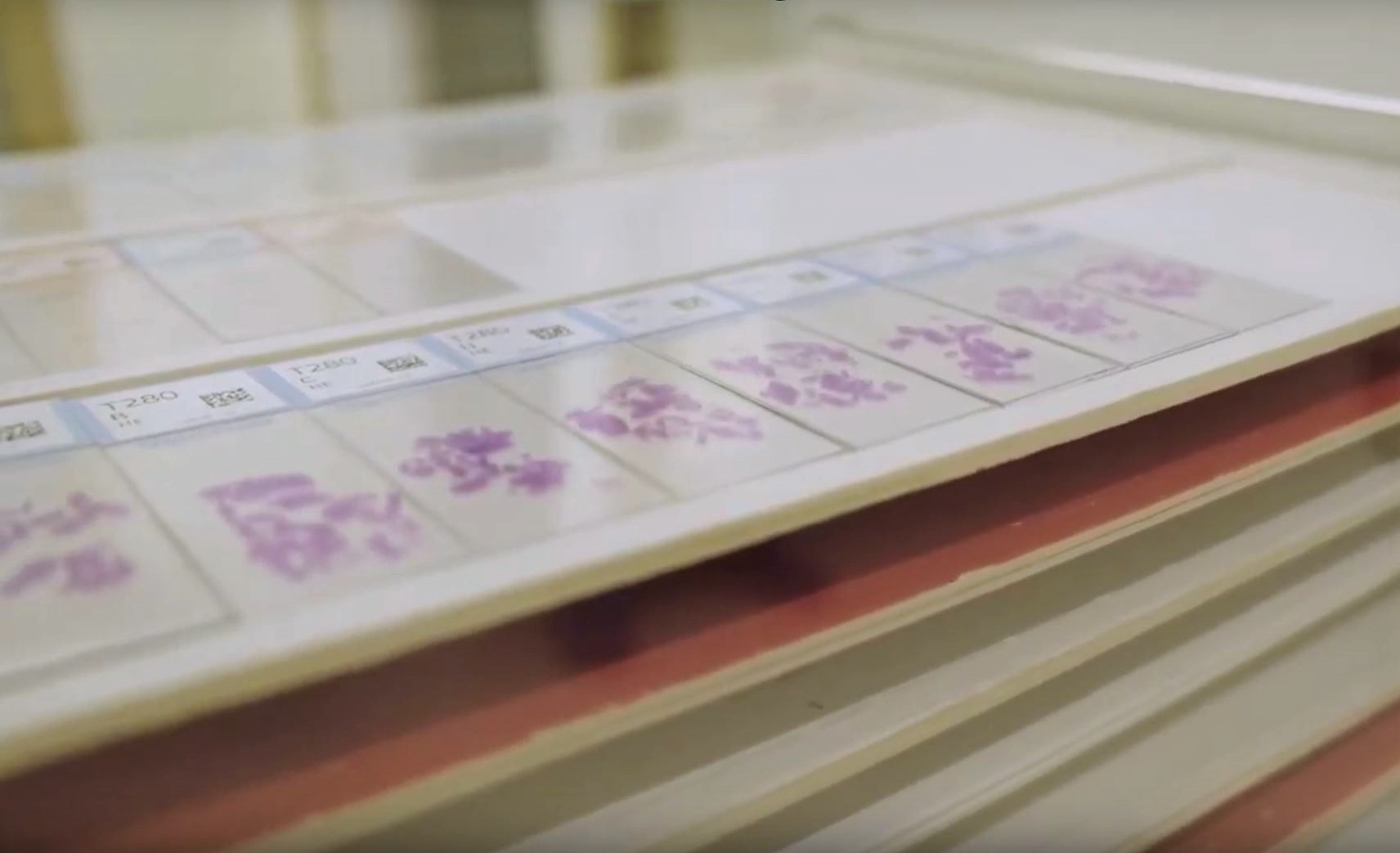

That’s certainly possible. And as a managing director in an imaging company engaged in regional digital pathology programmes around the world, I could tell you lots about the real benefits it can deliver. From being a precursor to the application of artificial intelligence, to supporting faster diagnoses, and allowing instantaneous access to opinions and reporting capacity from pathologists who might be many miles away, digital pathology has enormous potential.

And as pathology services remain under pressure to restructure, regionalise and consolidate, digital provides a means to help reshape structures where services have been historically isolated in a single organisation.

The challenge is that technology cannot do any of this successfully alone. Unless people with decision making authority give rigorous thought to appropriate service design, workflow, clinical strategy, and to the intricate requirements of different specialities, then the chances of realising the real service transformational benefits that digital technology can enable are slim.

When digital could be damaging

A recent conversation I had with one cellular pathologist challenged my own thinking on the subject and reminded me about the dangers of viewing technology as a solution in itself.

Luisa Motta is a pathologist and strong advocate of the potential for digital to help to make things hugely better for a discipline faced with an insurmountable workload and massive resource pressures as it challenges to recruit clinical graduates and as much of the existing workforce approaches retirement.

But she is rightly concerned that adoption of digital and the consolidation of services it can enable, could be hugely damaging if done in the wrong way.

The creation of regional pathology hubs and pooling of scarce resources, has long been an ambition in healthcare worldwide. For example, Lord Carter made a strong case for consolidating pathology services to “improve quality, patient safety and efficiency” in his 2008 independent review of NHS pathology services in England.

As regional approaches now start to emerge, for Motta, and I suspect for many other specialist pathologists, the thought of being moved away from the hospital to a business park off a motorway is unsettling. And, I’ve learned, that’s not because they aren’t willing to work as part of a regional network, it’s not a protectionist approach to their own hospital’s resource, and it’s not because they are resistant to change.

It’s because they want to defend a vital mechanism of communication between the pathologist and the clinician which is instrumental in decisions around patient care.

Don’t use digital transformation to sever the links

To alleviate such concerns, those leading transformation need a detailed understanding of how different pathology specialities operate and interact with clinicians as part of the clinical, surgical or patient pathway. They need an accurate understanding of the profiles of different hospitals. They need to make sure they protect knowledge networks where geographical proximity is important. And they need to ensure that relocation and consolidation of resources does not detract from the value a service can provide, improvements to services, research or the ability to discuss individual patients.

Consolidation and transformation must follow clinical strategy, and that may vary from one hospital and region to the next. Some regions, for example, may have hospitals with responsibility for specialist pathways and areas of high complex surgery. For specialist pathologists like Motta, the idea of moving pertinent pathologists outside of the hospital makes no sense, as the colocation of consultants and the lab is beneficial to promote discussion. In these complex areas, consultants actively visit the lab to see the surgical specimen, not just a slide or an image, before it is dissected and discuss it with the pathology team – something difficult to replicate through a report on a digital image from somewhere on a business park.

In more straightforward reporting cases that only rely on slides, such relocation is less of an issue. But in specialist pathways and areas of complex surgery, some pathologists are concerned that digital transformation could sever links and take them out of the clinical conversation. And in some cases, if the clinical dialogue is damaged, they are concerned that the service itself could be taken over by another provider if it consequently becomes ineffective. As Motta told me: “We cannot consolidate to the detriment of patients or the development of the service. Patients could be put at risk if we can’t discuss things which are pertinent to the case.”

In large and complex institutions like the NHS, it is important to continually challenge leadership structures to ask if they have the right knowledge, skills and commitment needed.

Get it right first time

Many pathologists like Motta do of course fully recognise the very restricted financial envelope in the NHS, and the consequent need to save money. But the primary driver cannot be one of estates or financial gains, in their view.

The bigger opportunity is to use digital to achieve regionalisation that allows quicker access to specialist opinions as part of the first report, rather than the creation of review, after review, after review.

For many pathologists, the main reason to consider transformation should be to eliminate duplication in systems, where one pathologist refers a report to the next, and to the next, until several weeks may have passed in diagnosing a patient’s illness. The real opportunity is to streamline pathways and develop a workflow that adopts the principle of getting it right first time.

We should not apply a single strategy

Making this happen effectively is pinned on having the right strategy that addresses the requirements of different services locally and regionally, so that we don’t end up in a situation where physical backlogs are converted to digital backlogs.

Used properly, digital pathology enables bespoke solutions to be developed to solve the particular clinical issues that a pathway in a region may be experiencing.

If you understand the workflow and the pathway and have gone through individual pathways to identify duplication – it is possible to make informed decisions on where pathology labs need to be created, consolidated or retained, and how they can be connected via digital pathology to ensure the optimum use of resources – particularly workforce.

For Motta, people get too obsessed about how many labs we need and the cheapest way of creating them, rather than looking at workflow, pathways and what makes sense, what doesn’t and how develop a system that gets it right first time.

She also believes, that at some point consolidation can become too much consolidation meaning the benefits start becoming risks. So, there is an optimum point for consolidating that allows you to work with partners, and that incorporates a system where the first report is timely, accurate, complete and allows the patient to move to the next part of the pathway. A deep understanding of the workflow in the region, which specialisms are movable from the hospital and which are immovable, is essential.

Do we have the right leaders?

I can state from experience that in the UK there are many people currently leading transformation who certainly get this. As digital pathology starts to move beyond discussions on whether microscopes, slides or digital images are equally effective, and to the reality of transforming services so they can cope with demand and better serve patients, I am working with many inspiring individuals who are passionate about making this work.

But there can be no room for complacency. In large and complex institutions like the NHS, it is important to continually challenge leadership structures to ask if they have the right knowledge, skills and commitment needed. It is something that Matt Hancock, the UK’s health and social care secretary, alluded to in a January 2020 keynote address on the urgent need for modern technology.

And it is something recognised on the ground. Cellular pathologists like Motta, for whom I have a great deal of respect, need to play a leadership role at this time of substantive transformation, to ensure they are understood and heard.

Motta believes that pathologists are still not necessarily represented at boards, and in salient papers that describe workforce requirements in cancer pathways. And where this is the case, the status quo needs to change. Pathologists who are singularly focussed on addressing the immediate backlog of reporting also need to be given scope to play a crucial role in policy shaping and decision making at the national, regional and local level.

They need to be able to raise the conversation beyond one where technology is seen as the answer, to one of ensuring a conscientious analysis of how we can improve pathways, before we then use digital pathology as a tool to get there.

As Motta said to me: “Digital pathology is like any tool – including dynamite. In the right hands it can be really good and useful. In the wrong hands it can be quite destructive. Some managers think that installing digital pathology will solve all their problems without even modifying or adapting patients’ pathway. That’s not going to work.”

This article was originally published in The Pathologist