In 1997, Clayton Christensen published his master piece, The Innovator’s Dilemma, describing how successful companies focus too much on customers’ current needs, and fail to adopt new technology that will meet their customers’ unstated or future needs.

Shifts to new technologies, often mentioned as disruptive innovations, are very easy to recognize in retrospect. A few famous examples are the transition from film to digital in photography and radiology, Skype over traditional telephones, and the streaming of music and videos from Spotify or Netflix. Although most new technologies are detected early and agreed on as the next industry standard, many vendors and users continue to espouse the old technology until a certain tipping point is reached.

I would argue that this is what we are seeing in today’s adoption of digital pathology. Digitizing the pathology workflow is surely a disruptive innovation since it is likely about to change the way cancer diagnosis is performed, with benefits achieved in terms of sharing, increased efficiency and integrated diagnostics. Despite the general view that digital pathology is the new, up-and-coming technology, some pathologists remain uncertain. I believe many parallels can be drawn between the adoption of smartphones and the digitization of pathology. The true paradigm shift will happen when users change their focus from hardware to the benefits of state-of-the-art software, providing a true user experience that simplifies the pathologist’s daily work.

Adoption accelerates, eliminating the use of the old products

The theory of disruptive innovations grows from the distinction between sustaining technologies and disruptive ones. The former produce incremental improvements in the performance of an established product. For example, light microscopes might offer enhanced optical quality and ergonomics. Disruptive innovations, on the other hand, are innovations that usually offer worse product performance in the short term but provide users with other value-enhancing benefits. These other benefits in disruptive innovations typically make the products simpler and more convenient to use, which drives their adoption.

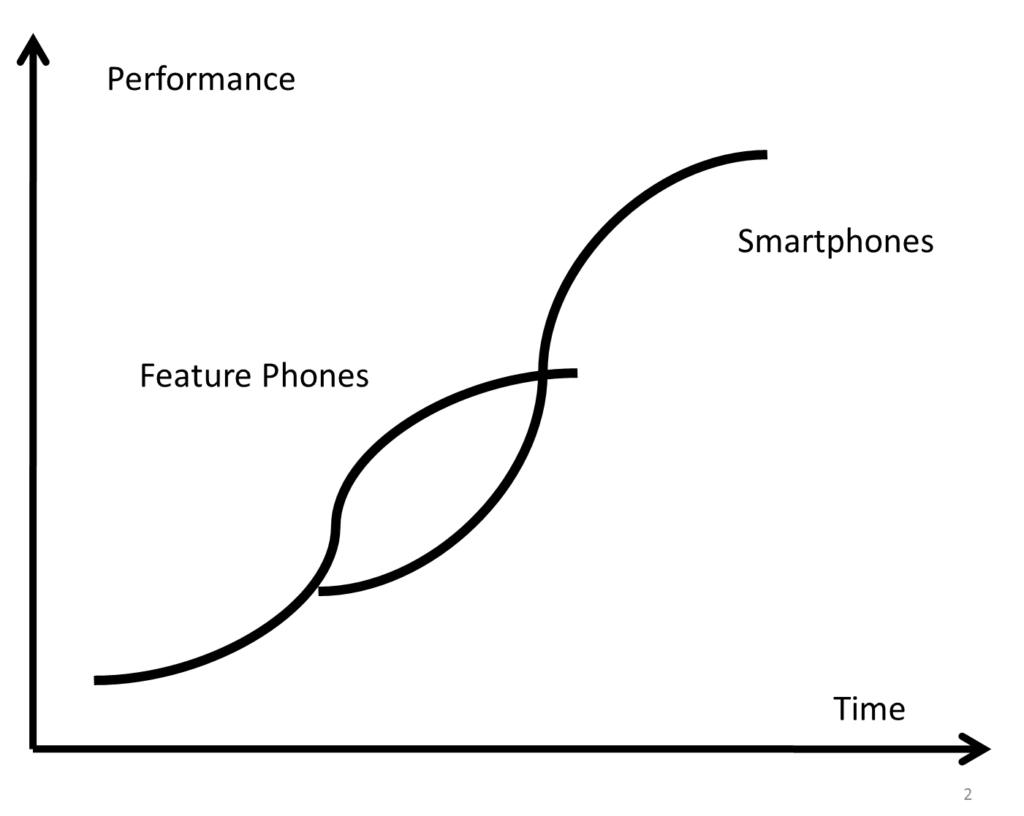

As the performance of a new product innovation improves, adoption accelerates, steadily eliminating the use of the old product. This trend can currently be seen in the adoption of digital pathology, which is often implemented in incremental steps, involving an intermediate stage when the microscope is used in parallel with digital review until it is retired completely.

Patterns from smartphone adoption recognized in pathology

One obvious example of a new technology reaching its tipping point was the rise of smartphones over feature phones, triggered by the introduction of the iPhone in 2007 and 2008. Before the launch of the iPhone, user preferences were centered on capabilities such as smaller size, longer battery time and a broader variety of mobile phones from which to choose. Industry-leading vendors like Nokia listened to their customers’ demands and kept their focus on capabilities related to powerful hardware, including features such as cameras and music. When the iPhone was introduced, user preferences quickly shifted from better features to enhanced user interaction—the focus turned from capabilities in hardware to state-of-the-art software.

Although smartphones, in many ways, were initially inferior to feature phones (Figure 1), users preferred the benefits of the new technology, which in turn drove their adoption, and smartphones now outperform feature phones in most areas, with the exception of battery time.

Figure 1. Illustration of smartphones initially being inferior to smartphones, but were adopted since users valued other benefits[3].

However, the entry of software companies into the digital pathology arena has provided the industry with new capabilities for enhanced user interaction, system stability and support of heavy workloads. Applications are now available that allow pathologists to review digitally at a faster rate than with a microscope. Benefits such as digital sharing, automatic mitosis counting and side-by-side image comparison have been enabled and become increasingly obvious thanks to the speed and usability of the software.

As use preferences in digital pathology also shift from features to usability and speed, we now seem to have reached the same tipping point as smartphones did with the introduction of the iPhone.

Additional information of interest

Christensen also mentions that in the initial years after a new technology appears, “the dominant companies almost always have a closed, proprietary architecture—one in which the design of one component depends on the design of all other components” and “that is because the technology isn’t yet very well understood. But as it becomes good enough for what customers in the less-demanding end of the market need, it gets overturned to open architectures.” [1]

The same development from proprietary file formats and closed architecture to open standards occurred in the digitization of radiology 15 years ago and we now see the same pattern emerging in the digitization of pathology. Users have started demanding that vendors follow standards such as DICOM and HL7 to support multiple scanner file formats and provide tight integration with any LIS, PACS and EMRs.

Sources

- Harvard Magazine, 2014, Disruptive Genius, Craig A. Lambert ’69, Ph.D. ’78, access: http://harvardmagazine.com/2014/07/disruptive-genius

- Christensen, Clayton M. (1997), The Innovator’s Dilemma: When New Technologies Cause Great Firms to Fail, Boston, Massachusetts, USA: Harvard Business School Press, ISBN 978-0-87584-585-2.

- Image source: http://disruptiveinnovation.se/?p=73